Learn About How Screwless Dental Implants Work

Outline:

– Implant structure: fixtures, connections, surfaces

– Placement concept: planning, surgery, loading

– Design differences: retention methods and microgaps

– Biomechanics and materials: forces, tissues, longevity

– Practical guidance and conclusion

Implant Structure: What Holds Everything Together

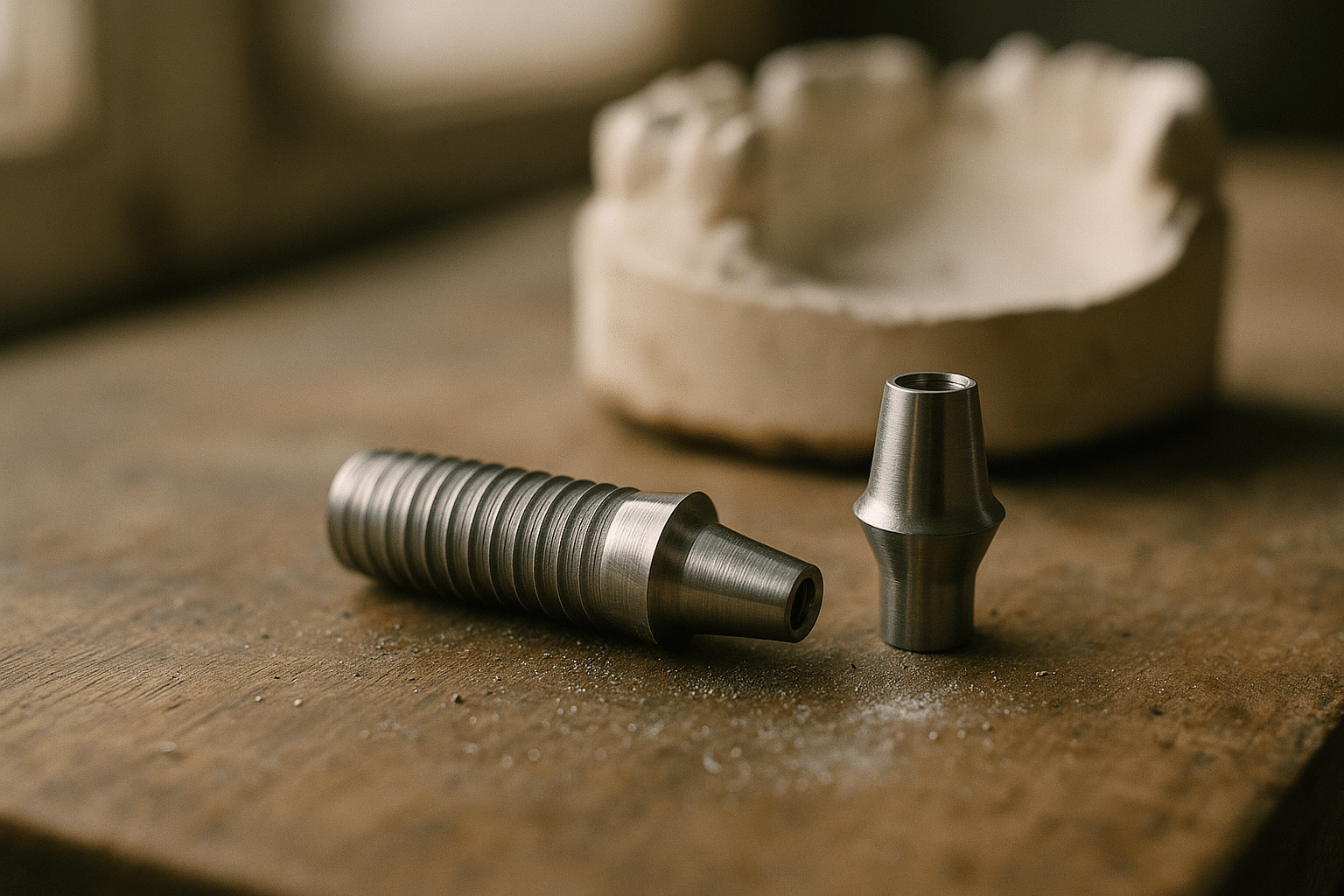

The structure of a dental implant is a triumph of engineering made to cooperate with biology. At its core is the fixture, a threaded cylinder or tapered form crafted to mimic a tooth root. The external thread pattern cuts into bone for primary stability, while the overall macro geometry—tapered, parallel-walled, or hybrid—distributes load during chewing. Inside the fixture, the connection receives an abutment that supports the visible crown. Depending on the system, that connection may be a conical (Morse-type) taper, an internal hex, or another keyed geometry designed to resist rotation and micro-movement.

Surface engineering matters. Moderately roughened titanium (often created through grit-blasting and acid-etching) increases the area for bone contact, encouraging osseointegration—the stable, direct bone-to-implant interface. Typical healing timelines range from several weeks to a few months, influenced by bone density, site preparation, and patient health. Zirconia implants also exist, valued for their color and biocompatibility, though clinicians often cite titanium’s long track record and favorable modulus of elasticity for stress distribution.

At the prosthetic level, abutments may be prefabricated or custom-milled to shape the emergence profile and support the soft tissue seal. The microgap where abutment meets fixture is a focal point because even tiny gaps can harbor biofilm. Internal conical connections are prized for their intimate fit and reduced micromovement. Cement management is another structural consideration; residual cement around a subgingival margin can irritate tissues, which is why many clinicians prefer retrievable, mechanical retention. Screwless designs are explained differently than traditional implants.

To visualize the parts, think in layers:

– Fixture: the root analog integrated in bone

– Connection: the internal geometry that locks components

– Abutment: the connector shaping the soft tissue path

– Crown: the chewing surface designed for function and aesthetics

Each component’s tolerances, materials, and fit quality influence longevity. Data from long-term cohort studies often show survival rates exceeding 90–95% at 10 years when planning, hygiene, and occlusion are well controlled. In other words, structure is not only about shapes—it is about precision, biology, and maintenance living in harmony.

Placement Concept: From Planning to Stable Integration

Successful implant dentistry begins long before the surgical day. The placement concept integrates diagnosis, prosthetic planning, imaging, and guided execution. Cone-beam CT scans reveal bone volume, density, and anatomical landmarks such as sinuses and nerves. From there, a prosthetically driven plan determines position, inclination, and depth to align the implant with the intended crown. Digital wax-ups and surgical guides help translate this plan to the mouth, minimizing deviation and improving accuracy.

Primary stability is the immediate mechanical grip that keeps a fixture still while bone heals around it. It is influenced by bone density (Type I–IV), osteotomy design, and implant macro geometry. Many clinicians reference insertion torque (for example, 25–45 Ncm) and stability measurements such as ISQ values to judge whether immediate temporization is prudent. Immediate loading is common when torque and ISQ are adequate, occlusal forces are controlled, and parafunction is managed. Otherwise, a short healing phase allows the biology to “catch up.” Screwless designs are explained differently than traditional implants.

Surgical workflows can be conventional freehand, pilot-guided, or fully guided. Fully guided protocols, when accurately fabricated and used, can reduce angular and depth errors and protect critical anatomy. Site preparation balances under-preparation for stability against overheating or excessive compression that could impair healing. In grafted or sinus-augmented areas, conservative torque targets and staged loading reduce risk.

Good placement also means respecting soft tissues. Adequate keratinized mucosa facilitates hygiene and comfort. A provisional crown or healing abutment can contour the gingival profile, shaping an emergence that is cleansable and natural-looking. Postoperative instructions—gentle cleaning, short-term soft diet, and follow-up checks—protect the forming bone-implant interface.

Key planning checkpoints clinicians often use include:

– Restorative end in mind: crown-first positioning

– Risk mapping: smoking, diabetes, bruxism, and bone quality

– Occlusal scheme: distributing forces to minimize overload

– Maintenance plan: tailored hygiene and recall frequency

When these steps align, the placement concept becomes a predictable pathway from scan to smile, marrying engineering with biometrics to lower complications and support long-term function.

Design Differences: Screw-Retained, Screwless, and Cemented Approaches

Implant-supported restorations are commonly categorized by how the crown or prosthesis is retained. Screw-retained crowns use a central prosthetic screw to clamp the abutment or crown to the fixture; they are retrievable and avoid subgingival cement, but they require proper screw access positioning and careful torque control to reduce loosening. Cement-retained crowns can optimize esthetics by eliminating an access hole, yet they demand impeccable cement management to avoid peri-implant inflammation from excess residue.

Then there are friction-fit or locking-taper concepts that aim to eliminate the central retaining screw. In these, a conical interface creates a cold-weld-like seal through high-contact friction, sometimes supplemented by geometry that resists rotation. The advantages often cited include a tight microgap, reduced micromovement, and straightforward occlusal design without an access channel. The trade-offs can include technique sensitivity for seating and specific protocols for retrieval using vibration, special tools, or controlled tapping. Screwless designs are explained differently than traditional implants.

When comparing these designs, consider the following practical dimensions:

– Microgap control: conical friction fits may reduce bacterial colonization potential if seating is precise

– Retrievability: screw-retained is inherently straightforward; screwless requires defined retrieval methods; cemented can be challenging if glued subgingivally

– Occlusal design: screw channel affects aesthetics and contact points; friction-fit and cemented allow unbroken morphology

– Complication profile: screw loosening vs. decementation vs. interface wear

Evidence suggests that both screw-retained and well-managed cement-retained solutions can reach high survival rates when protocols are respected. Friction-fit approaches show promising soft tissue stability when the interface remains immobile and clean. Choosing among them hinges on prosthetic access, tissue anatomy, esthetic demands, and the clinician’s familiarity with the system. In anterior cases with limited interocclusal space and high esthetic demands, a friction-fit or cemented approach may simplify the emergence profile; in full-arch scenarios, retrievability of screw-retained frameworks is often valued for maintenance.

No single design universally outperforms others across all scenarios. The right choice is contextual, shaped by anatomy, function, and the maintenance plan agreed upon with the patient.

Biomechanics, Materials, and Tissue Response: Why Details Matter

Chewing forces are not gentle; peak bite forces can exceed several hundred newtons, and lateral vectors challenge the bone-implant interface. Biomechanically, implant length, diameter, thread pitch, and platform switching all influence how forces travel into cortical and cancellous bone. Wider platforms can reduce stress intensity in softer bone, while platform switching (a narrower abutment on a wider fixture) relocates the microgap inward, supporting crestal bone preservation.

Titanium grades 4 and 5 are widely used for their strength, corrosion resistance, and favorable modulus. Zirconia offers a metal-free option with high stiffness and smooth surfaces that may limit plaque accumulation. Surface topography affects early bone healing: moderately rough surfaces tend to yield faster and stronger osseointegration compared to polished surfaces. Reported marginal bone loss often falls around 0.5–1.5 mm in the first year after loading, stabilizing thereafter when occlusion and hygiene are well managed. Screwless designs are explained differently than traditional implants.

Soft tissue biology is equally vital. A stable, non-inflammatory cuff of keratinized mucosa around the abutment enhances comfort and cleansability. Emergence profile design should avoid over-contouring that traps plaque; gentle convexity with accessible embrasures helps. Polished transmucosal surfaces and careful polishing protocols limit biofilm retention.

Complications in the real world revolve around biomechanics and maintenance. Common issues and mitigations include:

– Overload: adjust occlusion, consider splinting, increase implant number

– Screw loosening (for screw-retained): verify torque, use appropriate screw design, refine occlusion

– Decementation (for cemented): control cement volume, use retrievable cements in accessible margins

– Interface wear (for friction-fit): adhere to seating and retrieval protocols, schedule routine checks

Longitudinal studies frequently report high survival and success rates when these factors are respected, often above 90% over 10–15 years. The through-line is not a single device feature but a chain of well-executed decisions—from imaging to occlusion—that together create a resilient system.

Practical Takeaways and Final Thoughts for Patients and Clinicians

Whether you are weighing your first implant or optimizing complex care, the practical path forward is clear: align the prosthetic plan with biology and choose a retention method that fits the case. Patients benefit from understanding how parts fit and why maintenance visits matter. Clinicians benefit from consistent protocols, documentation, and patient-specific risk mitigation. Screwless designs are explained differently than traditional implants.

Use this conversational checklist to anchor decisions:

– Goals: What matters most—retrievability, esthetics, or simplified maintenance?

– Anatomy: Is bone volume, smile line, and soft tissue thickness compatible with the plan?

– Retention: Does screw-retained access align with esthetics, or would friction-fit/cemented improve contours?

– Hygiene: Can the patient clean under the margin and around contacts easily?

– Risk factors: Bruxism, smoking, systemic health, and medications

– Follow-up: Agreed recall intervals and radiographic review schedule

For many single-tooth cases, screw-retained designs give straightforward access for future care, while friction-fit concepts can deliver a tight interface and a clean occlusal table when used with precise technique. In esthetic zones, emergence profile control and cement management are pivotal. In full-arch therapy, maintenance planning and retrievability often guide the choice toward mechanically retained frameworks.

Patients can ask their provider to explain how their implant’s interface works, how it will be cleaned at home, and what signs should trigger a check-up. Clinicians can enhance outcomes by standardizing torque verification, documenting ISQ values when relevant, and calibrating occlusion under function rather than static contacts alone. Across designs, the fundamentals—bone-friendly surgery, stable soft tissue, and biofilm control—drive longevity.

In short, clarity beats hype. When planning and execution are aligned, contemporary implant systems provide reliable, comfortable function that integrates into everyday life. Your most valuable tool is an informed conversation that matches the design to the mouth it serves and sets clear expectations for care over the years.